This article is part of a series centered around the members and work of the Northwestern University Cello Ensemble.

Michael van der Sloot is a Canadian cellist and composer, and a recent graduate of Northwestern University (M.M. ’15) where he studied with Hans Jørgen Jensen and participated in the Northwestern University Cello Ensemble. His piece Shadow, Echo, Memory was recorded by the ensemble as part of their new album of the same title, which will be released by Sono Luminus on July 29.

Q: What was the original inspiration behind Shadow, Echo, Memory the title work of Northwestern University Cello Ensemble’s new album?

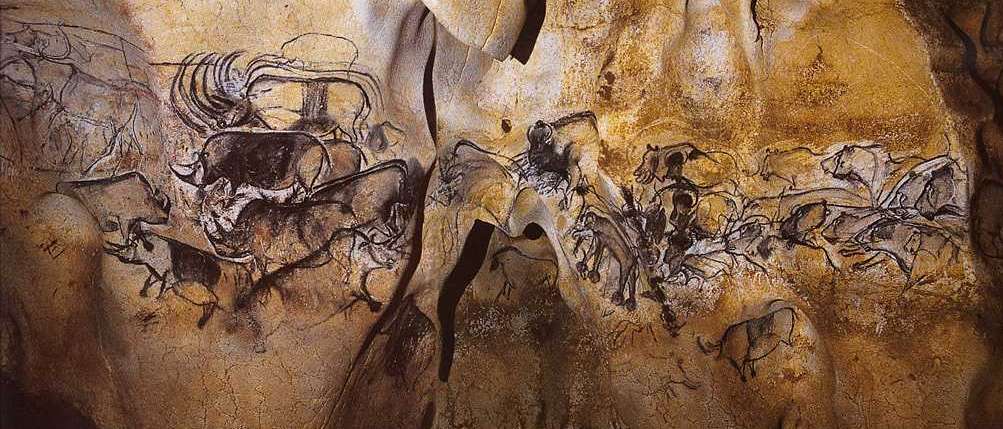

A: The original inspiration came from prehistoric paintings in caves in Europe. I think I first saw them in a TV documentary when I was a little kid and I was immediately fascinated. That fascination resurfaced during my time at Northwestern, and I felt an urge to write something new that drew upon that inspiration. I knew that writing for the cello ensemble would be the perfect chance to work out some of those ideas.

Q: What in particular appeals to you about cave art and how did it initially capture your attention?

A: First of all, many of the paintings are very visually striking and beautifully crafted. But, I would love to go into one of these caves to see them in their original context. It’s one thing to view the paintings reproduced two-dimensionally on a page or a screen; it would be much different to witness them in the cave itself. Their size, their placement, how they are lit in the darkness, where they are located in the cave, the natural contour of the rock underneath, etc. These factors would all very much affect the way these paintings are experienced. I was really intrigued by the context, so in the music, I wanted to create that experience, rather than represent the images themselves.

I was also inspired by how incredibly old this art is. When you think about the Ice Age world they lived in compared to now, it’s very alien. Many of the animals depicted have been extinct for tens of thousands of years. However, looking at the images there’s still an apparent familiarity. These peoples’ art still manages to connect us with them in a very human way.

Q: Can you explain more about the sounds you invented for the cello ensemble, which seem to come from this other world from the past? How do you as the composer find yourself relating to such a world? What is it about your impression(s) of this world (or worlds) that you wish to convey to the listener, and how do you go about achieving that?

A: To go along with the theme of foreign vs. familiar, I knew I needed to use the cello in more unconventional ways to produce a greater variety of timbre. For instance, half of the ensemble tuned their strings down to a lower pitch so that I could get a darker sound that – when massed – could sound like an entirely different instrument. In the opening of the piece, players create a sound similar to that of dripping water by lightly striking a muted string near the bridge with the wood of the bow. It’s actually quite difficult to get a consistent sound that way, but it sounds very cool when it’s right. I used harmonics extensively (perhaps recklessly), and produced them using a variety of different means to give the music a more other-worldly sound. In another section, cellists imitate the sound of imaginary flutes by playing behind the bridge, playing high on low strings, and forcing the contact point to slide all over the string. The cello can produce a very airy, breathy tone that way. Those are a few examples of some of the extended techniques in this piece. There is very little “traditional” cello-playing in the piece, but all of the sounds are indeed produced by the cello.

Q: Can you tell me more about how the caves might have been used for spiritual events?

A: One theory is that the caves themselves were used for shamanistic purposes, and that the art was part of these rituals. Such rituals would have been intended for communication and/or travel between different worlds, likely by means of inducing an altered state. I liked the idea of creating and stepping into an alternate reality in this piece, and that’s the interpretation that I worked into the music. But, my music is only based on my own impression from the paintings and what I’ve learned about them, and one of the most awesome aspects of this art is that it leaves a lot to the imagination. We could envision countless contexts in which this art was made, because nobody actually knows for sure. Some of these sites were re-visited by different prehistoric artists several millennia apart. I doubt the later artists would have fully known the original, authentic meaning and purpose of their predecessor’s art, either! Nowadays, many experts who study prehistoric art avoid interpreting it because nobody will ever be able to truly do so with any scientific certainty. However, we can certainly appreciate still this art as magnificent evidence of humanity’s rich imagination and creativity in a very different time, and marvel at its ability to stimulate our own imaginations today.

Q: How did the fact that you were writing for cello ensemble affect your compositional process, from a conceptional point of view? Is the musical meaning you create in any way contingent on the instrumentation? What challenges are there in writing for cello ensemble?

A: I appreciated having such a large homogenous ensemble to work with, because it’s much easier to blend the instruments that way. At the same time, I had enough cellists that I could thoroughly utilize many different extended techniques simultaneously. The challenge was creating a sound world that transcended the cello world while maintaining at least some notion of uniformity. Putting some of these very different effects together in an organic way proved to be much more difficult than I expected.

Q: In Shadow, Echo, Memory you make extensive use of aleatoric compositional techniques and flexible notation (i.e. the paleolithic flute solos), giving the performers a great deal of control and flexibility over what they play. What thoughts do you have about the role of the performer in your piece and how did you decide to write in this way?

A: Part of the decision to write the piece in an aleatoric framework was for practical reasons. Time is always valuable in the rehearsal and recording process, so I wanted to cut out as much technical ensemble work as possible (tuning, synchronizing entrances, locking rhythms, etc.). The sooner we could get past the nuts and bolts and work on the sound world I wanted, the better. Besides, the indeterminacy helped create the textures we needed much more simply and naturally than precise notation would have.

On a musical level, I also believe in giving as much power to the performer as possible. I like it when players feel they can harness their own creativity and intuition when working on my music, rather than being a slave to the details on the page. There’s almost nothing more flattering to me than hearing different interpretations of my own music.

Q: Briefly describe your compositional process. Does it vary from piece to piece or have you by now felt out a generalized way to get things done?

A: Like many composers, I need to give myself some clear and rigid parameters early on to organize and channel my ideas. Then, it’s a matter of trying to fit those ideas into those parameters in the most cohesive and concise way possible. This planning stage takes the longest and rarely involves staff paper. Lots of scribbling down thoughts during breakfast, humming to myself while walking the dog, brainstorming in the shower, etc. By the time I’ve got the bigger picture figured out, the details on the page usually come very quickly – almost in a deluge. I don’t trust what I’ve written the first time around, so I’ll always take a healthy break after finishing a first draft, then I’ll dive back into the piece with a fresh imagination and a more critical lens. From there, I’ll usually break it down and reconstruct it again three or four more times before I consider a piece ready.

Q: Since you are such an accomplished cellist, does your knowledge of specific technical aspects of cello playing help you come up with creative ideas when composing or does it actually limit your imagination?

A: I usually like to write what I like to play, and generally, that means either very wildly or very delicately. The cello has awesome extremes that too often go under-utilized (by both performers and composers, in my opinion). I tend to think of my string writing in a very physical way, and my pieces are frequently a result of working things out on my instrument by myself. Also, many of my favorite techniques and effects that I use in my music are byproducts of time I should have spent working on other things in the practice room. It’s usually more fun to explore weird sounds than refine the nicer ones. Overall, I’d say my experience as a cellist has certainly helped my creativity as a composer – but I suppose that perhaps my own personal biases as a performer may limit it a bit from time to time!

More information can be found on van der Sloot’s website: www.michaelvandersloot.com

The Northwestern University Cello Ensemble is currently working on their album Shadow, Echo, Memory, which will be released by Sono Luminus on July 29. Please enjoy this sneak peek below, and be sure to become a fan on Facebook and follow them on Twitter.

海外直営店直接買い付け!★ 2020年注文割引開催中,全部の商品割引10% ★ 在庫情報随時更新! ★ 実物写真、付属品を完備する。 ★ 100%を厳守する。 ★ 送料は無料です(日本全国)!★ お客さんたちも大好評です★ 経営方針: 品質を重視、納期も厳守、信用第一!税関の没収する商品は再度無料にして発送します }}}}}}

https://www.bagssjp.com/product/detail-3927.html