Reinvention in the classical music world can sometimes be difficult. And yet, in a world that is constantly changing, reinvention has almost been necessary for survival.

Reinvention in the classical music world can sometimes be difficult. And yet, in a world that is constantly changing, reinvention has almost been necessary for survival.

Classical record-label Naxos understands this, perhaps better than most.

In the late 1980s, the record label Naxos was a bargain-budget name with a dicey reputation. True, it was recording lots of interesting repertory and selling it at cut-rate prices, but it was supposedly doing this by exploiting its artists, who were paid a flat fee, no royalties, and often not even enough money to cover recording costs. What kind of recording deal was that?

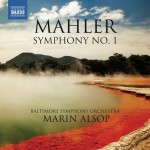

This year, Naxos is celebrating its silver anniversary — as one of the major forces in the classical music field. Today, cushy record contracts for classical artists are all but extinct, more and more artists are self-financing their recordings, and Naxos, offering significant brand recognition and the biggest international distribution network in the field, suddenly looks like a pretty good deal.

The savvy business sense of its founder, Klaus Heymann, is no longer seen as a liability; it’s enabled him to keep the company making money despite the fact that the classical recording business is changing so fast that every time I’ve talked to him over the past 10 years, Naxos has had a different primary source of revenue.

“We can’t live off CD sales anymore,” says the German-born Heymann, 75, speaking by phone from his base in Hong Kong. When Naxos began, Heymann proved that you could make money selling tens of thousands of copies of works nobody had ever heard of; as CD sales gradually declined, the company has variously relied on proceeds from digital downloads, audio books, and other ventures. Today, it looks to YouTube, where a tool called Content ID crawls the site, figures out how many of a given company’s videos are illegally posted, and – rather than removing the videos – calculates that company’s share of advertising revenue. “That’s become an income stream,” says Heymann, estimating that it covers about 75 percent of his recording budget.

“iTunes, Audible, SiriusXM,” he adds. “Wherever there’s a source of revenue, we squeeze it out.”

Twenty years ago, this kind of talk branded Heymann as a miser, a businessman exploiting artistic talent. Today, he’s often heralded as a visionary, a businessman using practical means to keep a valuable artistic resource afloat.

It is precisely this adaptability and foresight that has allowed Naxos to not simply survive but also thrive. Naxos has done its best to evolve with the times. Capitalizing on new opportunities that inevitably arise with new technological innovations and new channels of marketing & distribution. For example, last month Naxos announced an agreement with Clear Channel which would enable the Label to participate in all radio revenue streams, lending its expertise to programming the “Classica” station on iHeartRadio.

Taking advantage of opportunities such as these are what have enabled to build a “classical empire” that spans the globe, centered around its base in Hong Kong. In this interview, founder Klaus Heymann discussed some of the origins of the company:

Tell us about how you started Naxos.

It was just a commercial idea. At the time, in Hong Kong, a CD cost $150 but an LP cost $40. So I thought you could sell a CD for the price of an LP. So we licenced the first 30 albums from a guy in France. A few months later, they licenced the same recording to many others, so we decided to make our own productions. From there it was a struggle to be recognised as a quality label because [it was still considered that] cheap can’t be good.

How hard do you think it was to overcome that stigma?

It took a very long time in certain markets. England was the first market where the label was accepted because we had a very famous critic who wrote an article [saying] there was an alternative in Naxos. Then we started to get listed in the Penguin Guide and we got good Gramophone reviews. I would say it took 10 years for us to be recognised everywhere and it will probably take us another 25 years to convince those 90-year-old critics that we’re good.

Naxos, arguably, is one of the few organizations that has made it a point to embrace the unorthodox. In a field driven greatly by orthodoxy, that sets them apart. Whether it’s pioneering new business models for recording or promoting an unusual musical sub-genre via their albums, Heymann has pushed Naxos to demonstrate a range and variety in its musical capacity as a record-label. It hasn’t been all sunshine, but it has likely been the biggest contributing factor to the strength of its position today.

Read the full story – Naxos’s 25 years of reinventing itself

No comments yet.