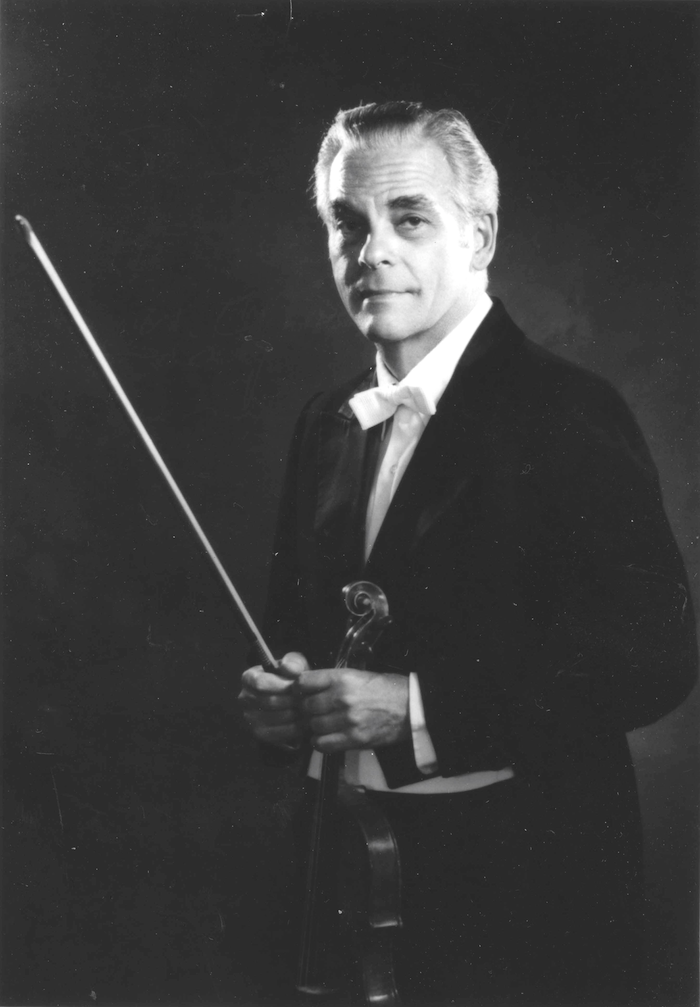

Earlier this week we released the first part of our exclusive interview with Ovation Press editor Norman Carol. In the continuation of this interview, Mr. Carol talks more about becoming a professional musician and a concertmaster.

String Visions: How does someone prepare to become concertmaster?

Norman Carol: Most of the time it just happens. You hear of an opening and take the audition. I was lucky enough to have had 3 years as a member of the Boston Symphony way, way back before doing some solo work. When I heard about an opening as a concertmaster I took the audition. I think it was, as far as I’m concerned, the smartest thing I ever did because I not only was able to make a very decent living at it but musically I had all kinds of challenges, not only performing but leading various people and getting involved with the audition process.

String Visions: Does having experience first as a member of the section benefit a future concertmaster?

Norman Carol: I think it probably helps but there are some young people who really have their heart set on being concertmaster right away. Some of them are fortunate enough to go right from school into a smaller orchestra as concertmaster. I know of several students from Curtis who only played in an orchestra at school and then wound up as concertmaster of an orchestra.

String Visions: For young musicians joining a major orchestra for the first time, what do they need to know?

Norman Carol: You need three sets of eyes:

- You have to always watch the conductor

- You need another set of eyes to look at the music

- Maybe the most important thing: you need a third set of eyes to watch the leader of the section.

If you’re in the violin section watch what the concertmaster is doing. I think it’s extremely important to be able to play in the same part of the bow in which you see the concertmaster or section principle playing. This is extremely important not only for a successful career but also in order to learn how and where you should be playing the music. If possible, you can even have a fourth set of eyes to observe what kind of fingerings the concertmaster is using. Although it is not always physically possible, it helps if you can do it.

String Visions: What does the first-time concertmaster need to know in order to fulfill that position’s responsibilities?

Norman Carol: First of all, I would say know the part cold before you even come to the first rehearsal. I don’t think there is anything more demoralizing to a section if they see that the concertmaster is not quite up to snuff as far as the part is concerned. I would also think that, somewhere along the line, you present some ideas as far as bowings are concerned even if that means asking another concertmaster for advice. I hate to use the term “listening to recordings” but for young people today that seems to be their modis operandi–listening to recordings. Just generally, use your musical instincts to play something correctly. However, above all else, the most important thing your level of preparation: to be ready and knowledgeable about the music… about what is in the part. Another thing you have to learn, depending on the standard of the orchestra, is how to communicate with the musicians in the orchestra and to be able to understand as quickly as possible what the conductor wants out of the music.

String Visions: Which of your own teachers had an especially large impact on you as a musician?

Norman Carol: I had two teachers that had an enormous impact, neither of whom were violinists. One was William Primrose: probably the greatest violist that ever lived, although he started out as a violinist. I had Primrose for chamber music when I was a student at Curtis, and I learned more from him than any other person. The other teacher that had an enormous influence on me was Marcel Tabuteau, principle oboe of the Philadelphia Orchestra. Tabuteau taught our string class at Curtis and by his own admission he knew nothing about the technical details of how strings play, but what he knew about music and phrasing was unbelievable. He was quite a character. We had the fear of God in us when we walked into his classes. As a young student at Curtis – and I was very young when I attended Curtis – just walking down the street, if Tabuteau happened to be on the other side of the street, for us it was like seeing God walk there. What an impact he had on us! The ironic thing is that we used to have those classes on Wednesday from 4:30 to 6:30 and for about maybe 35 years or so now I have had that same class. When I walk up the steps at Curtis I always get a chill, not believing that 35 years later, here I am doing the same thing Tabuteau did when I was a student.

String Visions: How has teaching impacted your career?

Norman Carol: Maybe most people won’t admit this, but I think teaching becomes a very selfish thing. I know when I first started teaching and needed to suggest something to the student, all of a sudden I would have to think: how do you do this, or why do you do this, and so forth. Then over the years you just learn to explain all of these things. This is why I’ve always believed that it becomes a very selfish commodity, because from teaching you learn so much yourself. Another crucial point to remember is no matter what the level of the student is, it is very important that the teacher approach the student with a great amount of courtesy. I think we forget perhaps some of the frustrations we had as young people trying to learn these stupid instruments we play, and this young person is going through the same things themselves. I think patience is very important with students, although I must admit I lose mine at times.

String Visions: What career advice do you give to students?

Norman Carol: I seem to repeat the same little speech to my students every year:

Every one of you here expects to have an unbelievable solo career. You’re gonna be the greatest violinist, violist, cellist, bassist in the world, but just in case that doesn’t happen, you are probably going to form one of the greatest string quartets in the history of music making and you’re going to have a fantastic career. Well, in case that doesn’t happen, there’s always the orchestra.

String Visions: Is chamber music experience important for orchestral musicians?

Norman Carol: I believe it’s the most important form of music they can play, because playing chamber music as a young student is really the precursor to playing a larger chamber piece like an orchestral work. It not only teaches you how to phrase but also how to analyze the music and accept suggestions and criticism from your colleagues. For people who play in an orchestra, I think perhaps it becomes frustrating that they don’t have enough time to play chamber music. I was very fortunate in being exposed to chamber music at a very early age; we go back to Primrose for that. I was always able to find time to learn and perform chamber music. As a matter of fact, when I finally did retire from the orchestra, I played in the Philadelphia Piano Quartet. A former colleague of mine in the Philadelphia Orchestra left the orchestra a number of years before I did and he decided to go to Florida to retire. He had this idea of inviting me down for a concert to see how it went and his wife was the pianist and we had a very fine violist. As a matter of fact, the violist’s name was LaMar Alsop, father of Marin Alsop the conductor. And that’s how it started. I went down just to play one concert. We hit it off and decided to put on a monthly series which lasted for about 11 years.

String Visions: What did you enjoy most about playing with this group?

Norman Carol: The four of us got along extremely well. We had a lot of fun together and we really enjoyed the repertoire that we were playing. It was not only a piano quartet but many times we had a soloist with the group. Doriot Anthony came down to play with us a couple of times, and Dale Clevenger, from the Chicago Symphony. We were able to expand to quintets and sextets and so forth. Occasionally we all did some solos on the chamber concert program. It was really a potpourri of music and very enjoyable. A lot of fun. We didn’t have a conductor to bother us either.

String Visions: Can you share a couple of the most memorable moments from your orchestral career?

Norman Carol: There have been so many experiences! Although I never really enjoyed touring that much, we had some wonderfully glorious moments. I remember the first time Muti took us to Naples, Italy to play. Naples was his home town, and on the very first time he came walking out on the stage, they wouldn’t let him start the program. The applause and the insanity was just unbelievable. Every time it calmed down, somebody would say something causing another eruption. That was wonderful. We had to go on for maybe 8 or 10 minutes before we were able to play the first note. I’ve met a lot of interesting people on tour. I met Madam Mao on my first to China, and on two different occasions. If you know a little about Chinese history, the first time the Philadelphia Orchestra was in China was in 1973. We were the first Western orchestra to go. It was just at the end of the Cultural Revolution and people were really starving for classical music at that time. On that tour we were not allowed to play certain composers such as Tchaikovsky. We went again in 1993 exactly 20 years later. Things had changed so dramatically in China. We went from seeing no automobiles on the street to streets having traffic jams with automobiles.

String Visions: What was one of the funniest moments playing in the orchestra?

Norman Carol: This is a true story. We were playing a summer concert up in Saratoga Springs where the orchestra was in residence for three or four weeks. In the middle of the performance we suddenly heard what we first thought was a gunshot sound. Those of us who were string players knew better. The strings of the violin are held on top of the bridge by a piece of gut that stretches very, very tightly on the back of the violin. And occasionally from age or wear and tear, this thing snaps, makes a huge noise, everything, everything falls apart. The strings are relaxed, the bridge falls, you can’t play. The gentleman whose violin this was just sat there with the violin on his lap. Ormandy continued to conduct and then he leans over to this man and said, “Don’t play.”

String Visions: That’s funny. Thank you so much for your time and your wonderful knowledge.

We hope you have enjoyed this two part interview with Norman Carol. To see a complete listing of his music with Ovation Press visit Norman Carol’s editor rofile

No comments yet.